So, you’ve made a short film. You’ve toiled and sacrificed. You’ve crowd-sourced and shed cinematic blood, sweat, and tears. You’ve begun the arduous and confusing process of submitting your masterwork to film festivals around the world. And, well, after waiting impatiently for several months, it seems nobody wants to screen it. It’s not getting the overwhelming acceptance you thought it would. What went wrong?

We get this question a lot. We here at Short of the Week screen a lot of short films—many, many thousands—some we find organically on the web and many more that are submitted to us every year. We watch so many films that the common mistakes that might otherwise go unnoticed, become giant red flags. Some of these mistakes are small and easily remedied. Others are deeply ingrained in more profound creative components such as narrative, structure, and theme. But all of them are avoidable if you know what to look for.

Now, a brief disclaimer: Every film is different, and in film as in art, rules are made to be broken—tastes among curators vary and there are always films that prove the exception.

1. Your Film is Too Long

This one is rather obvious. It’s called a “short” for a reason, right? Well, the issue is that most young filmmakers approach making a short with the structural lessons they’ve learned from watching features and long-form television. The result is a film that lacks the punch of an effective short and is also missing the depth of a feature. The pace feels wrong. And, online, where attention spans are so short, most have trouble finding an audience. Many offline festivals are going to balk at your long film too. Purely on a logistical level, 30 minute shorts are notoriously hard to program. A festival would much rather screen 3 x 10 minute shorts than your 27 minute film. As always, there are exceptions (we have a “long short” collection on this site after all). But, we’d offer the following aphorism that has been attributed to a plethora of historical figures: “If I had more time I would have written you a shorter letter.”

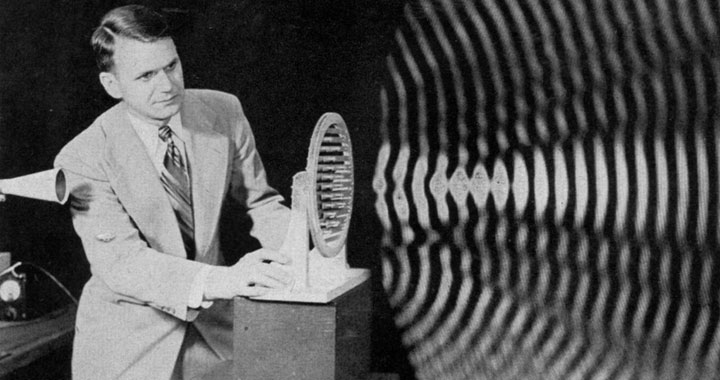

Check out Alexander Engel’s This Is It for a fast, condensed narrative.

2. Your Film Starts Too Slow

A short film (especially online) needs to hook a viewer fast and early. Seems simple, right? You’d be surprised how often short films forget this.

As a curator for a major online platform states, “In the context of having any desire for digital distribution, a slow or opaque beginning is mistake number one. (Opaqueness and intrigue/mystery are very different things. The latter is a good thing.) Conversely, don’t be proud, think about how your film will hook your audience in the first five seconds.”

You hear that aspiring filmmaker? You have five seconds! Which brings us to our next cinema sin…

3. Your Film Has Opening Credits

Nothing makes us want to eject from a short film faster than when it starts with a long opening credits sequence—we don’t care how cool those credits looks. This may sound harsh, but unless you’ve got a big name in the cast, nobody cares who was in your film, who made it, and who did the production design. Granted, we know a lot of people worked really hard on your film and they deserve credit. But stick those accolades and Kickstarter backers where they belong—in a brief sequence at the end of the film. And we do mean brief. Don’t artificially pad the runtime of your film with an elongated slow credit crawl. This is the kiss of death for an online short because it can make your film appear 2 minutes longer than it actually is. And, to online audiences, two minutes is an eternity.

4. Your Film Has Bad Sound

As camera technology gets better and better, the barrier to making your film look professional is getting lower and lower. Honestly, most footage shot today looks pretty darn good. But, forget the shallow depth of field and highlight control, and ask yourself: Does my film “sound” independent? Sound is the one technical aspect of short films today that is most often overlooked. Aspiring young directors obsess over cool camera angles and elaborately blocked shots, but, in doing so, they often give short shrift to the audio department. Sound is also incredibly important. It’s the thing people will notice only if it’s bad. Bad sound is distracting—it pulls the viewer out of the moment. This is especially true if a film is dialogue driven. We want to hear your characters speak, not the ambient sound of the room they’re standing in.

5. Your Film Has Bad Acting

Seems obvious enough. Bad acting will sink a film no matter how interesting the concept. But, poor acting goes beyond just a weak performance. It extends to “miscasting” as well. Something that is all too common in short films. One tell-tale clue that you’re watching a student film is that all the actors in it are 16-24 years-old. Many amateur filmmakers cast young people (i.e. their friends) in experienced character roles. The aging hitman? The world-weary waitress? Unless they have the transformative power of Daniel Day Lewis, someone in their 20s just can’t play those characters convincingly. Good acting starts with good casting.

6. Your Film Lacks Originality

Grief. Depression. Suicide. Hitmen. Post-apocalyptic wastelands. Zombies. There are a slew of story clichés, tropes, and settings out there—unless you’re planning on doing something different with established trope, avoid them. To be succinct: don’t make a film that looks and feels exactly like other films you already enjoy. If you’ve already seen these movies, chances are we have too. Either take a framework and expand upon it, or go in a completely different direction. I beg of you… please… not another movie about a Hitman who just wants to feel a connection with someone.

I also want to to single out films about loss or grief. While there are definitely exceptions, films that tackle these heavy topics frequently stumble. It’s a common miscalculation, especially by young filmmakers, to assume that watching people act sad is inherently interesting and dramatic. Well, after screening a figurative lifetime of student films featuring characters staring aimlessly at a wall, let me tell you, it isn’t. Things like grief and depression are dramatic when they’re part of what defines a character, not the driving force of a plot or story.

7. Your Film is Black and White For No Reason

This is a huge pet peeve of ours and several other high profile curators. We get it… you’re “artsy.” But, don’t make your film black and white just to prove that you’ve seen classic films. If you’re going to opt for a certain visual style, make sure there is a clear motivation for it—a definitive artistic reason. This could be attributed to other stylistic ticks as well. Some of the biggest offenders are the “fake” silent film or the film noir parody. Both these styles are really overplayed, especially by first time filmmakers. Got that, gumshoe?

8. Your Characters Are Boring

If your characters are doing things just because the plot dictates it, that’s a problem. This is common in a lot of “high-concept” films that never quite make it past the ingenuity of the premise. Yeah, you may have a cool sci-fi idea, but you have to make us care about the people we’re watching on screen too.

9. Your Film has Interesting Characters, but they Don’t Do Anything

The converse of the above is also true. We see a lot of short films that do the hard work of creating interesting characters and unique milieus, but then nothing really happens. It may sound like basic story 101, but you need to challenge your characters and make them uncomfortable. Safe is boring. While short films have the luxury of not wrapping up their narratives in a neat fashion, they still need to show change and an emotional arc. They need to give their characters challenges to overcome.

10. Your Film Was More Satisfying to Make than it Was to Watch

Okay. This is a tricky one to quantify and warrants some explaining. The desire to create something can be immense: filmmakers, after all, want to make films. And, so, in making a film, they can’t separate the process itself from the final product. To them, they see a story with a beginning, middle, and end—they see something that started as an idea on paper and made its way to the screen. They are attached to that personal journey, and in turn, are satisfied with where they ended up. But, an unbiased viewer, has no attachments, and thus they only can see the final product. The meta-narrative of how something is made is completely lost on those not involved. This goes into a larger point about objectivity. Yes, your film might be your baby. But, for everyone else, it’s just someone else’s kid. Learning to receive and accept unbiased feedback is one of the most important things a burgeoning filmmaker can do to aid their cinematic growth.

11. Your Film is Good Considering…

Made your film for $20? Shot it on an iPhone? All your actors volunteered their time? Guess what… no one really cares. I know that sounds harsh, but programmers don’t care about what hurdles you faced in realizing your creative vision. You can spend a week or 5 years on your film. All that matters is the end result. Further, highlighting any significant compromises you made can actually undersell your film and hurt your chances.

12. You Made Your Film in 48 Hours

Ever since the early aughts, “speed film festivals” have been really popular. And, it’s easy to see why—they’re a fun way to get together with your friends and actually make a finished product. But, very rarely do these quick turnaround films produce genuinely good movies. Again, there are always exceptions, but as a general rule of thumb, the more time you spend in pre-production, the better your film ends up being. 48-Hour Film contests are a great way to learn how to make films. Just don’t expect the end result to be a masterpiece.

13. You Didn’t Watch Other Short Films

This may shock you, but there are short filmmakers out there who don’t bother watching other short films. They may watch tons of feature films and television shows, but spend scant time exploring the medium and format they’re striving to create. This is akin to a sculptor who only researches oil paintings. If you’re planning to make a short film, you need to watch other short films—especially successful ones that are similar in the tone and style to your project. After all, everything is remix—we can only learn and grow by observing and adapting from others. Watch good and bad films. Decide what works and what doesn’t—what you like and don’t like. You’ve got no excuse—there’s an endless catalog of 3000 of the best short films right in front of you!

14. You List Meaningless Laurels

A red flag goes up when a film sent our way has a thumbnail image plastered with a dozen festival laurels that we’ve never heard of (or, even worse, the font is too small to make out the festival name). This happens more often than you think. Festivals can be great events, but not all festivals are created equal. As short film curators, we are pretty savvy on which festivals are the most prestigious. So, you’re not fooling us when you say you won “Best film at the Southwest Regional Lake Minnetonka Dance Film Festival.” Don’t overstate the importance of your festival pedigree, and we’ll respect the honesty rather than the attempt at self-importance. If you’re unsure of whether or not to include a laurel, take a look at this list of Academy Award qualifying festivals.

Now, a special note: One of the biggest red flags you can raise for programmers is listing Cannes on your list of festivals when your film was actually at the Cannes Short Film Corner. There are only 10 short films accepted into the Cannes competition each year, and we (as well as most programmers) know them all. Everything else is part of the Cannes Short Film Corner (which is a paid film market, not a competition). Listing the Cannes Short Film Corner in your laurels is effectively admitting that you know nothing. For a deeper dive on this, check out this anonymous piece on the subject.

15. You Made a Bland Profile Documentary

Documentaries can be powerful cinematic experiences. But, over the past few years, we’ve seen a flood of short “profile” documentaries flood the internet. You know the type: lots of ambient music, voiceover, and pretty b-roll about some artist with a quirky or odd hobby. These films all sort of feel the same to us. And, most lack a narrative arc to really stand out. We’re not saying you can’t make a good portrait doc. Rather, we’re saying that it’s now much harder to stand out.

But, don’t just take our word for it—Claudette Godfrey, a short film curator for SXSW, articulated a similar point in an interview with the American Statesman:

“The Internet has changed the life of a short film,” she says. “It used to be you make a short, show it at some festivals, and that was it. Now it can live forever because so many sites just want content or stuff to put on a Facebook page.” Which has led to a proliferation of “hundreds and hundreds” of three- to four-minute docs that Godfrey describes as “perfect for the Internet” but not necessarily something you would want to show on a big screen. “If it’s a three- or four-minute piece, I can tell within a minute if it is going to be one of those type of films,” Godfrey says. “It’s profile of an artist or a chef or somebody saying something sort of interesting. It’s the theory of least objectionable content, you know? And people will share that, and that is great. But it is not right for us.”

———

Okay. There it is—the common mistakes many short filmmakers make. Disagree? Have other ones you’d like to add? List ’em in the comments below.

Ivan Kander

Ivan Kander