It’s hard to consistently make work independently as an animator, and the rare creators who are able to ascend to this peak outside the byzantine realm of grants and government sponsorship are lionized names: Don Hertzfeldt, Bill Plympton, David Firth, CGPGrey. The rub, as always, is money, and on one side are YouTube creators that can produce frequently and monetize off ad revenue, and on the other side established artistic icons who have succeeded in cultivating an audience willing to pay them directly.

It’s been a while since a new member has joined these ranks, but I wonder if Steve Cutts, a UK animator/illustrator is set up to do so. The key is to reach a point where every new release is rapturously awaited and received, and with a string of viral hits behind him, and the certainty that this new film, Happiness, will achieve a similar state, Cutts is well on his way to collecting the audience loyalty, and establishing the artistic bona fides to attempt it.

Not that it appears he is really trying. Cutts isn’t particularly prolific on social media, doesn’t employ monetization on his YouTube videos, doesn’t charge for access to his work, nor is his merchandise shop very established. Charmingly though, this makes him an optimist’s case study on the point that what matters the most is the work, which continues to grow in both quality and acclaim. A creator of the internet, he has recently taken on notable creative commissions both popular (a highly coveted gig doing a couch gag for The Simpsons) and artistic (his 2017 music video for Moby earned a top prize at Annecy).

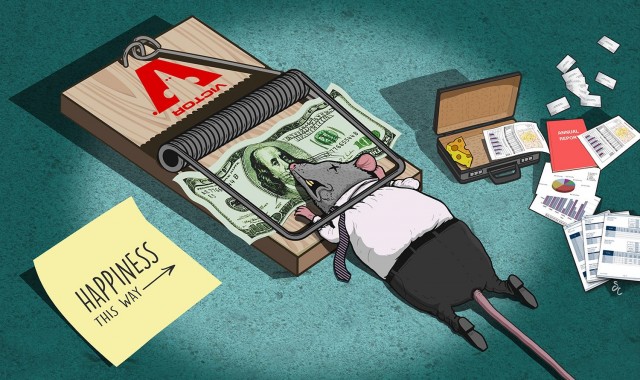

It is purposeful irony on my part to discuss economics at the outset of this review, considering the consistent anti-capitalist themes in Cutts’ art dating back all the way to his breakthrough work, 2011’s In the Fall. Happiness is his most full-throated damnation of the dehumanizing effects of capitalism and consumer culture, and is arguably his best work to date. Depicting a literal “rat race”, the film adopts the structure of Cutts’ most popular work, the S/W-featured and 25M+ viewed, Man, to tell a fast-paced linear montage of one rat’s quest for happiness through the tropes and traps of modern society.

In contrast to the thematic similarities that tie together his work, Cutts’ art style has shown remarkable diversity. His early ink style has evolved in disparate directions: from bright and flat (Any Time is Ice Cream Time) to darkly graphic (The Walk Home). Where They Are Now, a satirical imagining of retired cartoon characters gone to seed, and his award-winning Moby video show a nostalgic subversion of vintage cartooning styles. Throughout it all he has experimented with limited 3D objects in his largely 2D worlds, as well as mixed-media composites. His most recent Moby video, for In This Cold Place, is a perfect summation of these interests, as he is able to consolidate all these styles into one piece, using television as a thematic lens.

Happiness adopts the graphic style of The Walk Home, but marries it to the familiar vertiginous scale of his early work that compositing in his digital workflow enables. It is marvelous art, with a multitude of shots that deserve to be framed. Each scene is overflowing with information, from detailed backgrounds, to the cacophony of rat characters layered on top, and is, to my eyes, Cutts’ most mature and impressive work visually.

The unifying thread that connects so many successful independent animators is shock—a direct response to our still juvenile attitude towards animation cultivated by family-friendly commercial work. Cutts makes his hay through a subversion of this expectation in a way familiar to Adult Swim audiences, laced with pessimistic cultural criticism. Audiences love him for it, and Happiness is the apogee of this approach. Yet at this point his facile condemnation of society risks becoming juvenile in its own right. With each new work Cutts is a proving himself an exciting and popular artist—it will be interesting see going forward if the diversity and evolution he’s shown us in his craft will extend to his themes.

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi