It is unusual for us to feature a film that is so broadly recognized—Day of Rage: How Trump Supporters Took the U.S. Capitol has over 7.5M views on various platforms and that severely undercounts its spread. If you follow American politics at all, it is likely your feeds were inundated in the early summer with praise for this 40min film from the NYTimes in-house Visual Investigations team. Media cycles are shorter than ever but, for a solid 48 hours, it felt like this piece was all anyone could talk about on Twitter.

We debated covering the film in June and the fact that we didn’t had little to do with objective analysis on our part of its worthiness. It was more a confluence of overwork for our team and laziness on my part. By the time we got our act together, it felt like the moment for recognition had passed. Yet, the film covers one of those events that will, henceforth, be recognizable to many by just its date—1/6. So, like 9/11 before it, we will in perpetuity have anniversaries to mark. Today marks the first of such anniversaries and political and journalistic entities have lined up wall-to-wall coverage today to mark the “insurrection”. So, apologies for adding to the maelstrom, but, fresh off making it onto the Oscar Shortlist, we’ll join the chorus—Day of Rage is a spectacular work of visual non-fiction, one that, in its technical rigor, timely subject, and overwhelmingly impact marks the coming-out-party for a new form of non-fiction visual journalism.

Footage from open sources—social media posts and citizen journalists, make up the majority of the film.

I’m going to assume that you can suss out my ideological feelings towards the event in question, and, as someone who is not a political commentator, I want to sidestep narrow questions of what is “learned” from the content of the film, or discussion of its symbolic importance as a “defining document” of an episode in national history. What I want to do instead is recognize its lineage and contextualize what a monumental achievement the project is—in the scale of its labor, the technical process around its production, and the artistry of its formation.

Calling Day of Rage the “coming-out-party for a whole new form of non-fiction journalism” implies that it is not a wholly original endeavor. Indeed, it is not—it is a culmination of recent trends in what is called Open Source Investigations (OSI). Alternatively known as Online Open Source Investigations (OOSI) or, originally, Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) and sometimes referred to as “digital forensics”, what all these terms refer to is the process of using data from a wide variety of sources to piece together clearer pictures of newsworthy events. Originally this meant social media posts and user-generated footage, but, as the discipline became more sophisticated, these investigations began to incorporate satellite imagery, police scanner audio and bodycam footage, and other obscure sources. Not all visual material is found-footage either, 3D modeling, data visualizations, narration, and other produced elements are increasingly popular tools in these works, used to supplement viewer understanding. The “open” in the phrase means both that the sources of this video or audio evidence were culled from accessible places like social media, but also that the discipline itself is open—that anyone with sufficient curiosity and skill could participate in active communities surrounding key events, organized via social media tools.

The international collective, Bellingcat, is a key innovator in this space and has been important in codifying the tools and techniques of the emerging discipline. They are also an important resource in organizing and educating prospective investigators via their accessible guides. The same can be said of Storyful which is a pioneer of social-media journalism and is where Malachy Browne, one of the two credited directors of Day of Rage, worked before departing to the NYTimes in 2017 and becoming one of the founding members of its Visual Investigations unit. In the subsequent 4 years, the team has produced dozens of investigation videos on prominent stories, many of which have produced real-world effects. Their reconstruction of the timeline of Ahmaud Arbery’s murder was a pivotal piece of evidence in a recent court case, and their reconstruction of both Breonna Taylor’s killing and the shootings by Kyle Rittenhouse illuminated for audiences the facts behind otherwise confusing official accounts. Internationally, the team’s investigations into the export of Italian-made bombs into Yemen caused a huge public outcry and forced the government to stop the practice, and their investigation into the killing of Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi Arabian agents arrived at a pivotal moment when the U.S. Government looked poised to accept the Saudi’s fraudulent cover story.

In contrast to the Breonna Taylor film or the Kashoggi investigation where sources were lacking and the team is often looking for obscure clues that will serve as the puzzle piece that unlocks a bigger picture, the investigative techniques behind Day of Rage, are not that sophisticated. As the logline from the Times indicates, there might not have ever been a scene of political violence more well-documented than 1/6. What differentiates the film from other of its ilk is pure scale—thousands of hours of source material from participants and citizen journalists, plus the NYTimes going to court to unseal police bodycam footage. Collection, time-syncing, and geo-mapping all that footage was the notable technical challenge, but once accomplished the film presented a sizeable curation problem.

A logical structure for Day of Rage easily presents itself—follow the timeline of the event itself—but within that structure comes thousands of individual decisions on what to prioritize. Editing becomes the key skill as the film team must decide on which clips to highlight any given point in the timeline. Tracking back and forth in time would introduce unnecessary confusion for the viewer, so interesting footage had to be sacrificed if it could not slot into the temporal flow of the story. That same principle extends to geography—each location of incursion becomes a separate scene, and the team cross-cut between the scenes in order to develop an understanding of events happening simultaneously.

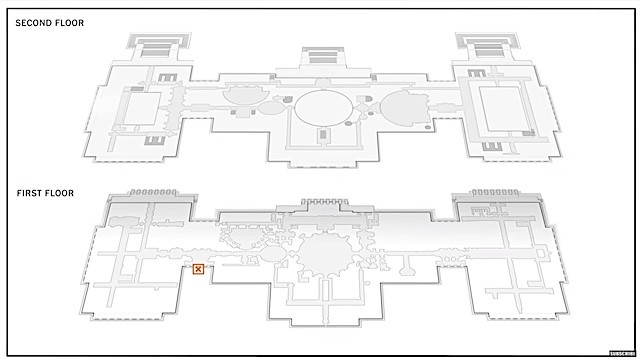

Two things impose order on this skillful presentation of raw footage. First, the script, narrated by Malachy Browne, adheres to journalistic practices of story building: establishing context, advancing conflict, explicating events. Browne’s voice is dispassionate, but authoritative, as he describes what is being seen. Second, are 3D models of the Capitol Building which situate the various scenes and at times sharply define the stakes at individual locations of violence within the larger context of the event.

While these elements lend a traditional journalistic feel to the documentary, more Frontline than Film Festival, the result is undeniably compelling. The inherent tension of the temporal flow, the drama of the catastrophe narrowly averted, means that the film plays more akin to a thriller than a piece of explanatory journalism, and the footage itself is gobsmacking—intimate and raw, the pure pathos of the participants and the unmistakable fear of the out-matched defenders lends a visceral to the film that easily carries a viewer across the lengthy runtime.

Both as an explainer of 1/6, and as a gripping viewing experience, Day of Rage is an unqualified success. Taking the skills of a relatively nascent team, operating in a relatively new journalistic format, and using them to produce the definitive document on one of the biggest news stories of 2021, the NyTimes has accomplished something noteworthy independent of the event it covered. As a favorite in the upcoming Oscar race, we look forward to increasing recognition and acclaim for Day of Rage in the coming weeks, and will see if this coincides with increasing utilization of OSI techniques in documentary projects of all sorts in the future.

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi