I am fascinated by notebooks. Keeping one has never been a habit of mine, but I’m envious of those who do, and endlessly delighted when I’m able to flip through them. Snippets of inspiration, casually drawn sketches, even mundane observations—what’s in a notebook feels closer to a direct window upon the creative mind at work than any finished artistic product can. Especially with artists I admire, there is also the surreptitious thrill of seeing ideas that will one day fully flower, captured on the page in embryonic form.

The Windshield Wiper, the highly anticipated short film from animation star Alberto Mielgo, reminds me of my fondness for notebooks. Not due to any direct evocation, but because it is spiritually similar—the product of a gifted artist filtering their recollections and gathering material over time in raw, even hasty sketches. Drawn from the artist’s observations and experiences as a globe-hopping creative, and self-produced over the course of six years, the short is a series of vignettes that feels like a notebook has been turned over and shaken out. While there is something quixotic about trying to transpose the serendipity I love about notebooks into such a punishingly exact form as animation, Mielgo has accomplished something very close to that in this gorgeous, meandering treatise on Love.

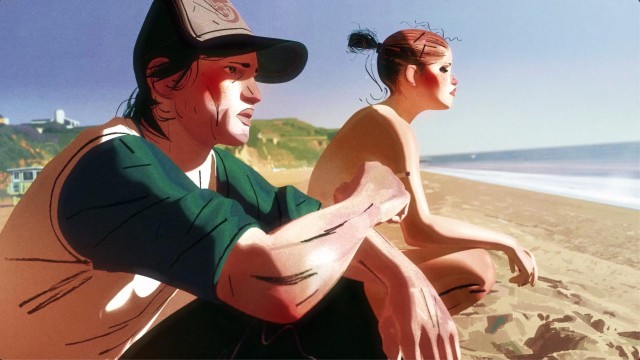

A middle-aged man in a café serves as the framing device for the film as he proposes a naive question of, nonetheless, enormous implications—“what is Love?”. The following 13 minutes examine that question in evocative and open-ended scenarios ranging from the bloom of initial attraction to elderly partners separated by death. In between, there is courtship and sex, missed connections and despair. Threaded throughout is a generational critique, as Mielgo interrogates the changing definition and customs of love throughout time. Love is enormous, love is indefinable, but love is also specific and shaped by context. Mielgo attempts to situate himself and the viewer as an outside observer to its ever-changing pattern.

As with most vignette films, how effective you find the scenes will vary—I found one reoccurring scenario, where two potential lovers fail to notice each other at the supermarket because they are too absorbed in their dating apps, to be a rather tired treatment of digital-influenced alienation. However, another quick scene that plays out over text messages, I found unbelievably poignant. It depicts a young lover letting slip the depth of their attachment only to face the dreaded “…” staring back at them. Without fail though, each scene is lovingly rendered in an exquisite cinematic style designed to provoke maximum emotion.

That stylishness is of primary appeal to many of the director’s rabid fanbase, which numbers over 120k followers on Instagram and which counts Barry Jenkins as a member. His production company, Pastel, joined the project in 2019 and was critical to helping it to completion. An artist and commercial director of repute for many years, Mielgo’s star has been on the rise due to his heralded film, The Witness, which was a standout entry in the first season of the Netflix anthology series, Love Death + Robots, and his work on the acclaimed feature, Into the Spiderverse. His artistic style has attracted many admirers in animation-corners and is tremendously fresh, depicting a world recognizably our own, but with a razor-sharp aesthetic sensibility. The process he uses is not groundbreaking. For The Windshield Wiper, Mielgo painted all the film’s detailed backgrounds in Photoshop then the animation team, led by his longtime friend Leo Sanchez Barbosa of Leo Sanchez Studio, keyframe animated 3D characters into the scenes. Yet it produces an uncanny effect—stylized, but not fantastical, cinematographic, but not wedded to the bland photorealism of gaming.

There is a naturalism to the characters, that, at first blush, is often mistaken for rotoscoping, but Mielgo protests that his approach is, in fact, very traditional. Recent articles at Cartoon Brew and AWN.com dive into closer detail on the film’s technical aspects, and in both interviews, he equates his process with how golden-era Disney productions were made, only with a result that is both modern, and impossibly cool. It is this tension between realism and fantasy that I suspect is the appeal of his work. On the one hand, it is a fantasy of sorts, full of stylish locales worthy of a lifestyle influencer’s timeline and populated by gorgeous characters in hip styling set in dramatic compositions. And yet it is also recognizably real—in a medium defined by abstraction on the independent end, or cutesy, family-friendly gloss on the high-end, Mielgo dares to pursue a fidelity to life that is adult and unabashedly sexy. The Windshield Wiper, coming from a very personal place, and adapting many of Mielgo’s own experiences, is perhaps the clearest demonstration to date of his artistic voice, full of clip-worthy sequences that befit a gifted professional image-maker, but married to an impressionistic format filled with searching, messy moments of relatable emotion.

Being familiar with Mielgo’s work, The Windshield Wiper has been high on my “must-see” list since its premiere last year at the Cannes Director’s Fortnight, and I’m pleased to say that I am not disappointed. Since then, it has qualified for an Oscar and landed on the Academy’s 15-film shortlist for the Best Animation Short Subject award. Voting for the final nominees begins at the end of this month and as part of the team’s promotional push, we’re honored to have the opportunity to share The Windshield Wiper with you as a limited release. Whether you’re new to Mielgo’s work or a dedicated fan, enjoy this chance to experience this passion project from one of animation’s most distinctive artists.

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi