I came to 夜車 (Night Bus) fairly late in its festival run, and thus a myth of the film had time to swell in my imagination. Completed in 2019, it has become one of those select few shorts every year that take on an out-sized profile due to their awards success—Grand Prix at Zagreb, Public Prize at Ottawa, Best Animation at Sundance—even a jury mention at Clermont-Ferrand. Normally we encounter short films early, before the hype, but I had let this decorated Taiwanese animation slide past me until its recent online debut via Condé Nast’s The New Yorker. It’s an odd sensation for me, approaching a short film with expectation, the same way one anticipates an acclaimed art-house feature film. Honestly, I imagined Night Bus would be similar in terms of temperament—subtle, poetic, and perhaps a bit inscrutable. It takes a few minutes into the short to get there, but I think it was the (first) dangling eyeball that dissuaded me from this notion.

By no means am I suggesting that Night Bus is lacking in artistry, its 2D cutout animation is impressively detailed, and the structure of its narrative is meticulously plotted, but the general storytelling and vibe of the film is surprisingly populist for such a decorated film. A pulpy noir mystery punctuated by scenes of gory violence, Night Bus is catnip to genre fans even while the precise genre it is playing in at any given moment is fluid.

Hsieh’s short is a classic whodunit mystery set on a bus

The film begins at a bus depot as passengers prepare to embark on a late-night ride down the Taiwanese coast. Hsieh assembles the cast of players: the driver, a well-to-do businessman and his pregnant wife, a haughty rich woman, two laborers, and a mysterious man in sunglasses. As the ride progresses, the passengers nod off. Upon being jolted awake, the rich woman notices her pearl necklace is missing. She demands the driver stop the bus as they attempt to discover the thief on the bus.

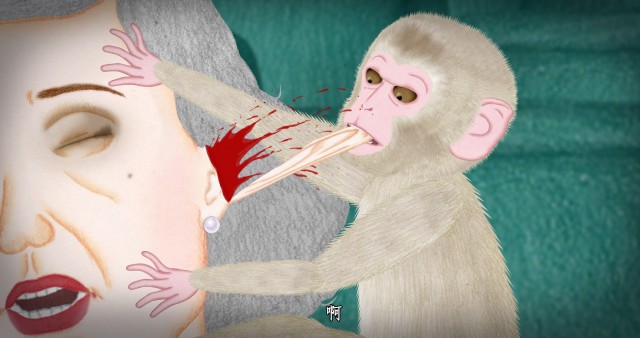

This inciting incident sets the plot in motion, a plot which takes an impressive number of twists and turns from this point, as a classic whodunit mystery gives way to a revenge thriller, which is itself undergirded by a melodramatic romance. Through it all are those moments of gore that are so over the top they perform the weird double move of both heightening the tension of the thriller, but also serving as an emotional release—their absurdity crosses into humor, eliciting audible reactions from the audience.

Despite the graphic nature of the violence, Hsieh insists “complex human emotions” are the focus.

A detractor will point to the film’s 20min runtime and the manipulative contrivances of the plot. It is true that Hsieh, in an attempt to establish an eerie and moody setting for this violent tale, indulges in atmospherics, especially in the film’s setup, and that will test online audiences. It is also true that without a charitable mindset, the machinations of the plot stretch incredulity, and that despite Hsieh’s protestation that, “the central theme of this film is on complex human emotions and interactions, not violence,” the violence is, in fact, exploitive and shocking for the sake of shock.

I myself don’t fully buy Hsieh’s claims about depicting “complex human emotions”, but the simple pleasures of the film are plain and immense—lovingly detailed animation, genre-blending of the highest order, lovers risking everything for one another, villains receiving comeuppance, a BABY MONKEY wreaking violent revenge! Critics can debate whether Night Bus is a masterpiece, but its status as a certified crowd-pleaser is undeniable.

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi